"Vellum of the Veiled Pulse: The Calf’s Last Breath in Stone and Green"

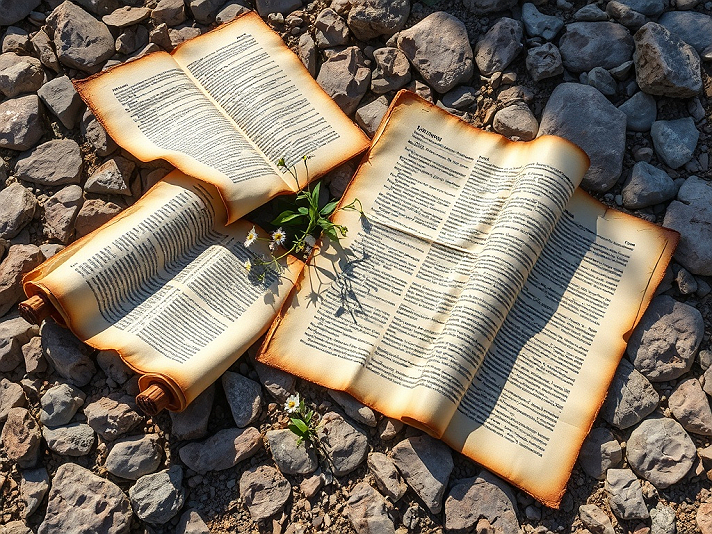

The photograph is a small, almost accidental resurrection. Four sheets of parchment (once scrolls, now unrolled and flattened by wind and weight) lie scattered across a bed of gray river stones. The stones are smooth, anonymous, the kind that have been tumbled for centuries until every edge is erased. The parchment is the color of burnt honey, its edges scalloped by fire or sun. The text is printed in a Cyrillic alphabet, dense and unyielding, but the words themselves are not Russian, not any language at all. They are a counterfeit scripture, a liturgy of nonsense that mimics the cadence of the Psalms without ever resolving into meaning. And yet, in the center of this ruin, a single green shoot has pushed up through the parchment, its stem threading through a tear in the page as though the word itself had germinated.

The composition is deliberate in its carelessness. The scrolls are not arranged; they have *fallen*. One lies on its side, half-rolled, its wooden spindle cracked. Another is pinned open by its own weight, the text facing the sky like a supplicant. A third has curled into itself, forming a shallow bowl in which a second plant (this one with two white daisies) has taken root. The fourth sheet is the largest, spread flat like a map, its surface cracked along the folds. The Cyrillic text is printed in two columns, the left headed “ПСАЛМЫ” (Psalms), the right “СЛОВО” (Word). The lines are packed tight, the letters sharp, but the sentences collapse into gibberish after the first clause: “Господь есть пастырь мой; я ни в чем не буду нуждаться…” gives way to “в зеленых пажитях; там где тени не касаются света…” and then to pure invention: “в тени крыл орла и в шуме крыльев ветра…” The text is a palimpsest of half-remembered verses, a scripture that remembers the shape of holiness but not its content.

The plants are the photograph’s quiet heresy. The central shoot is no more than three inches tall, its leaves still folded like prayer hands. It has grown *through* the parchment, not around it. The stem enters the page through a tear near the word “СЛОВО” and exits through another near “ПСАЛМЫ,” as though the text itself had opened to let it pass. The daisies in the curled scroll are smaller, their petals the white of old bone. They have rooted in the shallow depression formed by the parchment’s curl, their stems so thin they seem drawn with a pen. The stones around them are barren; no soil is visible, only the suggestion of dust. The plants have not grown *from* the ground; they have grown *from the word*. The parchment has become their earth.

The light is merciless. It is high noon, the kind of light that flattens shadows and bleaches color. The stones are the color of ash, the parchment the color of scorched paper. The green of the plants is almost violent in its intensity, a green that does not belong in this desert. The shadows of the leaves fall across the text like bars, caging the words even as the plants themselves escape. The photograph is a diorama of entropy and defiance: the scrolls are dying, the text is unreadable, the stones are eternal, and yet life (small, stubborn, absurd) has chosen this moment to begin again.

This is not the forest of the earlier series, where thorns cradled the word with tenderness. This is the desert returned, but softened. The canyon’s stone tablets were proclamations hurled down and abandoned; these parchment scrolls are letters that never reached their destination. They lie open, vulnerable, their message unreadable to human eyes. But the plants read them differently. The shoot that pierces the page is not destroying the text; it is *translating* it. The word has become compost, and the compost has become life. The daisies are not ornaments; they are the new scripture, written in chlorophyll and petal.

The photograph is a parable in miniature. The scrolls are the covenant broken, the text is the law forgotten, the stones are the wilderness that receives them. The plants are the remnant, the seed that falls on stony ground and yet (against all reason) takes root. The Cyrillic is a red herring; the real language is the green stem pushing through the tear, the white petal unfurling in the curl. The photograph does not ask us to decipher the text; it asks us to witness the moment when the text becomes unnecessary. The word has been eaten, digested, and reborn as something that does not need to be read to be true.

In the end, the image is less about scripture than about survival. The parchment will crumble, the ink will fade, the stones will outlast them all. But the plants will grow, however briefly, and in their growing they will carry the memory of the word into the air, into the light, into the next improbable season. The photograph is a quiet amen to that process: not the triumph of life over death, but the patient, almost invisible negotiation between them. The word is not lost; it has simply changed its medium. The desert has not forgotten the covenant; it has rewritten it in a language of root and leaf, a language that does not need to be understood to be obeyed.