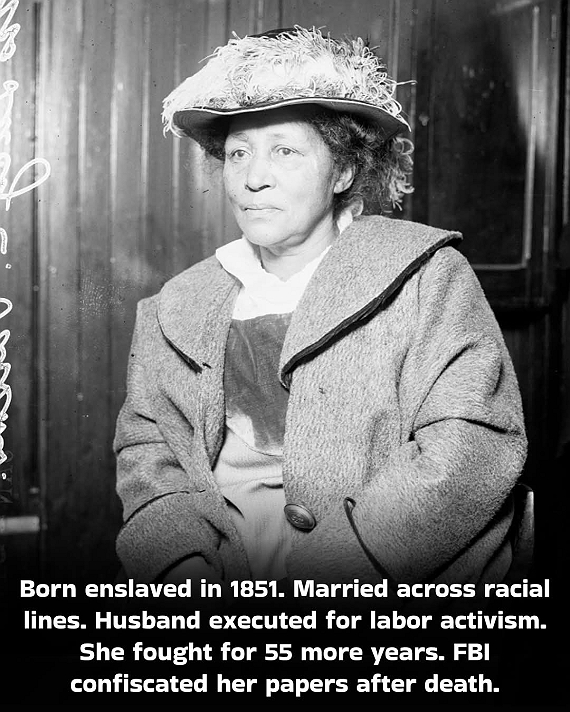

Born enslaved in Texas. Husband executed for labor activism. She fought for workers' rights for 55 more years. FBI confiscated her papers when she died.

They tried to erase her from history, but Lucy Parsons refused to vanish.

Born into slavery in Texas around 1851, she entered a world that told her she was nothing—no rights, no future, no voice. The exact circumstances of her birth remain unclear, deliberately obscured by a woman who understood that in America, her mixed African, Mexican, and possibly Native American ancestry would be used to diminish her.

But somehow, even as a young girl in bondage, Lucy must have sensed that history could be rewritten. Not by kings or generals, but by people who refused to bow.

When slavery ended in 1865, Lucy emerged from bondage into a country struggling to define what freedom actually meant. She taught herself to read and write—dangerous acts for a formerly enslaved woman in Reconstruction-era Texas, where white supremacy was rebuilding itself through violence and law.

In 1871, at around age 20, she married Albert Parsons—a former Confederate soldier who had renounced his past and become a fierce advocate for workers' rights and racial equality. Their interracial marriage was illegal in Texas and considered an abomination by white society.

The threats came quickly. Violence followed. They were driven from their home, their lives endangered simply for loving across the color line.

So they fled north to Chicago—a city of smoke and steel, where thousands of laborers toiled in dangerous factories for wages that couldn't feed their families, where child laborers lost fingers in machinery, where tenement fires killed entire families.

There, Lucy found her calling.

She saw the misery of working families. She saw mothers who worked all day in factories and returned home to care for their children with no rest. She saw men broken by labor that enriched others while leaving them destitute.

Her response was not quiet sympathy—it was fire.

Lucy began writing for radical newspapers, her words so sharp that editors said they could "cut chains." She spoke at labor rallies, on street corners, under bridges, anywhere workers gathered. Her speeches drew thousands.

"We must devastate the avenues where the wealthy live," she told crowds, "and make them understand that the misery they build upon has consequences."

The police began calling her "more dangerous than a thousand rioters." Chicago authorities followed her constantly, recording her speeches, tracking her movements. The press described her with a mixture of grudging admiration and open fear—a woman who would not be silent, could not be intimidated.

But Lucy didn't slow down. If anything, surveillance made her bolder.

Then came May 4, 1886—the event that would forever change her life: the Haymarket Affair.

A peaceful labor rally in Chicago, called to demand an eight-hour workday, turned violent when someone threw a bomb at police lines. Panic erupted. Shots were fired. When the chaos ended, seven police officers and at least four civilians were dead.

The authorities needed scapegoats. They blamed anarchist labor organizers—men who had advocated for workers' rights, men who had challenged the power of factory owners and politicians.

Among those arrested was Albert Parsons—Lucy's husband.

Despite a complete lack of evidence connecting him to the bombing—he wasn't even at Haymarket when it happened—Albert and seven others were convicted in a trial that was more political theater than justice. All were sentenced to death.

Lucy, only in her mid-thirties with two young children, became the face of the clemency campaign. She traveled, spoke, pleaded, and demanded justice with such conviction that even hostile newspapers couldn't ignore her.

On November 11, 1887, Albert Parsons was hanged along with three others.

Lucy, holding their children, was barred from seeing him one last time. She fainted outside the prison gates as the execution took place.

But when she woke, she did not retreat into grief. She transformed her loss into purpose.

For the next 55 years, Lucy Parsons became an unstoppable force.

She spoke across America—Boston, New York, San Francisco—warning of rising inequality, championing free speech, defending the poor. She edited radical newspapers. She organized marches. She was arrested more than 30 times.

In 1905—not 1883 as sometimes stated—she helped found the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a revolutionary union built on the belief that all workers, regardless of race, gender, or nationality, deserved dignity and power.

The IWW's motto became: "An injury to one is an injury to all."

Lucy lived those words.

The government feared her influence so deeply that police maintained files on her for over 40 years. The FBI monitored her activities right up until her death, seeing her not as an elderly activist but as an ongoing threat to the established order.

And they were right to be afraid—not because Lucy advocated violence, but because she advocated something far more dangerous: the idea that working people deserved dignity, that the system that enriched a few while impoverishing millions was neither natural nor inevitable.

By the 1930s, long after her contemporaries had faded from public memory, Lucy—now gray-haired and in her eighties—was still on the streets of Chicago, still giving speeches, still demanding justice.

She spoke at rallies supporting the unemployed during the Great Depression. She marched with younger activists. She never stopped believing that change was possible.

On March 7, 1942, at approximately age 90, Lucy Parsons died in a house fire in her Chicago home.

Even in death, her power frightened authorities.

Within hours, FBI agents and Chicago police raided what remained of her home and confiscated everything—her personal papers, her letters, her manuscripts, her decades of writings. Anything that could continue to inspire resistance was seized.

They feared her words more than they had ever feared her actions.

But they failed.

Because Lucy Parsons' words did not burn with her house. They lived on—in labor movements, in civil rights struggles, in every person who refuses to accept that injustice is inevitable.

Her ideas survived in the eight-hour workday she fought for (which eventually became standard). In workplace safety laws. In the rights of workers to organize. In the understanding that economic justice and racial justice are inseparable.

Lucy Parsons was born into slavery—told she was property, not a person.

She died as one of the most fearless voices for freedom in American history—feared by the FBI, monitored by police for decades, yet never silenced.

She wasn't just "the most dangerous woman in America," as authorities called her.

She was one of its truest patriots—one who believed that justice wasn't something granted from above by benevolent rulers, but built from below by ordinary people refusing to accept their oppression.

She loved her country enough to demand it live up to its promises. To insist that "liberty and justice for all" couldn't be just words—they had to be reality.

For 55 years after her husband's execution, Lucy Parsons kept fighting. Through old age, through poverty, through constant surveillance and repeated arrests.

She died in a fire at 90.

And the government was so afraid of her legacy that they stole her papers before her ashes cooled.

But her voice survived anyway.

It survives in every worker who organizes for better conditions. In every person who speaks truth to power. In every act of solidarity that crosses lines of race, gender, and class.

Lucy Parsons refused to vanish.

And 80 years after her death, her words still echo:

"We are the slaves of slaves. We are exploited more ruthlessly than men."

"Let every dirty, lousy tramp arm himself with a revolver or a knife, and lay in wait on the steps of the palaces of the rich."

"Never be deceived that the rich will allow you to vote away their wealth."

Words that cut chains.

Words the FBI tried to confiscate.

Words that lived anyway.

Because some voices cannot be erased—no matter how hard history tries. #Uhuru

They tried to erase her from history, but Lucy Parsons refused to vanish.

Born into slavery in Texas around 1851, she entered a world that told her she was nothing—no rights, no future, no voice. The exact circumstances of her birth remain unclear, deliberately obscured by a woman who understood that in America, her mixed African, Mexican, and possibly Native American ancestry would be used to diminish her.

But somehow, even as a young girl in bondage, Lucy must have sensed that history could be rewritten. Not by kings or generals, but by people who refused to bow.

When slavery ended in 1865, Lucy emerged from bondage into a country struggling to define what freedom actually meant. She taught herself to read and write—dangerous acts for a formerly enslaved woman in Reconstruction-era Texas, where white supremacy was rebuilding itself through violence and law.

In 1871, at around age 20, she married Albert Parsons—a former Confederate soldier who had renounced his past and become a fierce advocate for workers' rights and racial equality. Their interracial marriage was illegal in Texas and considered an abomination by white society.

The threats came quickly. Violence followed. They were driven from their home, their lives endangered simply for loving across the color line.

So they fled north to Chicago—a city of smoke and steel, where thousands of laborers toiled in dangerous factories for wages that couldn't feed their families, where child laborers lost fingers in machinery, where tenement fires killed entire families.

There, Lucy found her calling.

She saw the misery of working families. She saw mothers who worked all day in factories and returned home to care for their children with no rest. She saw men broken by labor that enriched others while leaving them destitute.

Her response was not quiet sympathy—it was fire.

Lucy began writing for radical newspapers, her words so sharp that editors said they could "cut chains." She spoke at labor rallies, on street corners, under bridges, anywhere workers gathered. Her speeches drew thousands.

"We must devastate the avenues where the wealthy live," she told crowds, "and make them understand that the misery they build upon has consequences."

The police began calling her "more dangerous than a thousand rioters." Chicago authorities followed her constantly, recording her speeches, tracking her movements. The press described her with a mixture of grudging admiration and open fear—a woman who would not be silent, could not be intimidated.

But Lucy didn't slow down. If anything, surveillance made her bolder.

Then came May 4, 1886—the event that would forever change her life: the Haymarket Affair.

A peaceful labor rally in Chicago, called to demand an eight-hour workday, turned violent when someone threw a bomb at police lines. Panic erupted. Shots were fired. When the chaos ended, seven police officers and at least four civilians were dead.

The authorities needed scapegoats. They blamed anarchist labor organizers—men who had advocated for workers' rights, men who had challenged the power of factory owners and politicians.

Among those arrested was Albert Parsons—Lucy's husband.

Despite a complete lack of evidence connecting him to the bombing—he wasn't even at Haymarket when it happened—Albert and seven others were convicted in a trial that was more political theater than justice. All were sentenced to death.

Lucy, only in her mid-thirties with two young children, became the face of the clemency campaign. She traveled, spoke, pleaded, and demanded justice with such conviction that even hostile newspapers couldn't ignore her.

On November 11, 1887, Albert Parsons was hanged along with three others.

Lucy, holding their children, was barred from seeing him one last time. She fainted outside the prison gates as the execution took place.

But when she woke, she did not retreat into grief. She transformed her loss into purpose.

For the next 55 years, Lucy Parsons became an unstoppable force.

She spoke across America—Boston, New York, San Francisco—warning of rising inequality, championing free speech, defending the poor. She edited radical newspapers. She organized marches. She was arrested more than 30 times.

In 1905—not 1883 as sometimes stated—she helped found the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a revolutionary union built on the belief that all workers, regardless of race, gender, or nationality, deserved dignity and power.

The IWW's motto became: "An injury to one is an injury to all."

Lucy lived those words.

The government feared her influence so deeply that police maintained files on her for over 40 years. The FBI monitored her activities right up until her death, seeing her not as an elderly activist but as an ongoing threat to the established order.

And they were right to be afraid—not because Lucy advocated violence, but because she advocated something far more dangerous: the idea that working people deserved dignity, that the system that enriched a few while impoverishing millions was neither natural nor inevitable.

By the 1930s, long after her contemporaries had faded from public memory, Lucy—now gray-haired and in her eighties—was still on the streets of Chicago, still giving speeches, still demanding justice.

She spoke at rallies supporting the unemployed during the Great Depression. She marched with younger activists. She never stopped believing that change was possible.

On March 7, 1942, at approximately age 90, Lucy Parsons died in a house fire in her Chicago home.

Even in death, her power frightened authorities.

Within hours, FBI agents and Chicago police raided what remained of her home and confiscated everything—her personal papers, her letters, her manuscripts, her decades of writings. Anything that could continue to inspire resistance was seized.

They feared her words more than they had ever feared her actions.

But they failed.

Because Lucy Parsons' words did not burn with her house. They lived on—in labor movements, in civil rights struggles, in every person who refuses to accept that injustice is inevitable.

Her ideas survived in the eight-hour workday she fought for (which eventually became standard). In workplace safety laws. In the rights of workers to organize. In the understanding that economic justice and racial justice are inseparable.

Lucy Parsons was born into slavery—told she was property, not a person.

She died as one of the most fearless voices for freedom in American history—feared by the FBI, monitored by police for decades, yet never silenced.

She wasn't just "the most dangerous woman in America," as authorities called her.

She was one of its truest patriots—one who believed that justice wasn't something granted from above by benevolent rulers, but built from below by ordinary people refusing to accept their oppression.

She loved her country enough to demand it live up to its promises. To insist that "liberty and justice for all" couldn't be just words—they had to be reality.

For 55 years after her husband's execution, Lucy Parsons kept fighting. Through old age, through poverty, through constant surveillance and repeated arrests.

She died in a fire at 90.

And the government was so afraid of her legacy that they stole her papers before her ashes cooled.

But her voice survived anyway.

It survives in every worker who organizes for better conditions. In every person who speaks truth to power. In every act of solidarity that crosses lines of race, gender, and class.

Lucy Parsons refused to vanish.

And 80 years after her death, her words still echo:

"We are the slaves of slaves. We are exploited more ruthlessly than men."

"Let every dirty, lousy tramp arm himself with a revolver or a knife, and lay in wait on the steps of the palaces of the rich."

"Never be deceived that the rich will allow you to vote away their wealth."

Words that cut chains.

Words the FBI tried to confiscate.

Words that lived anyway.

Because some voices cannot be erased—no matter how hard history tries. #Uhuru